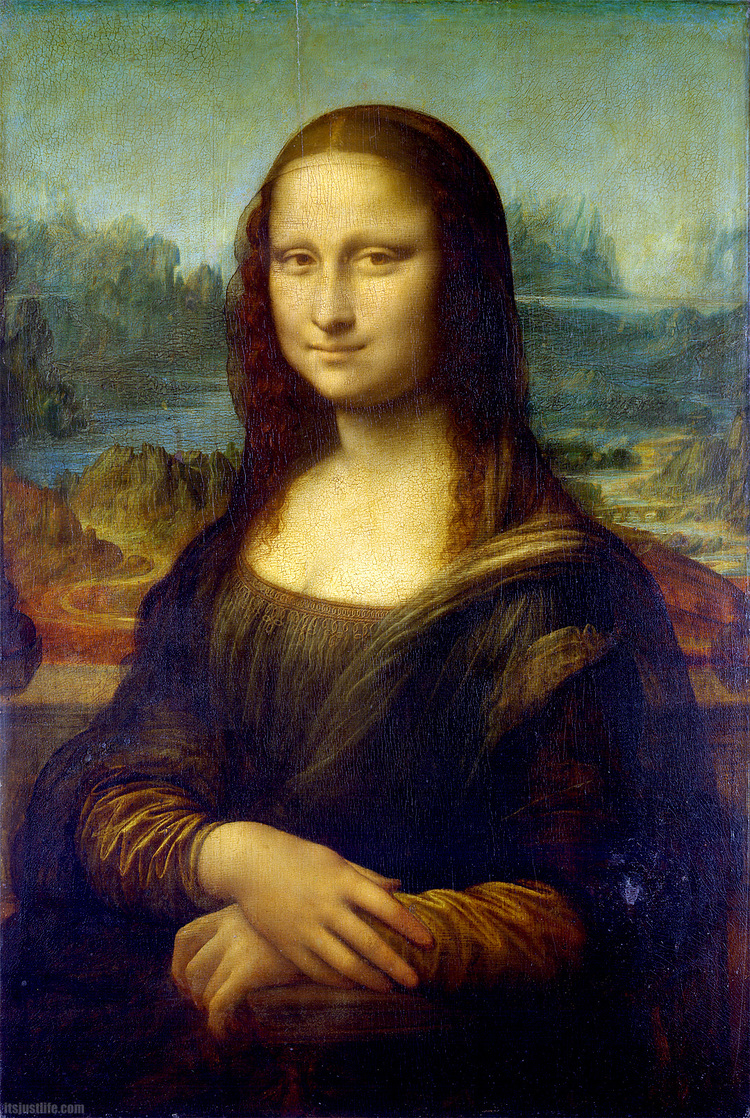

Mona Lisa

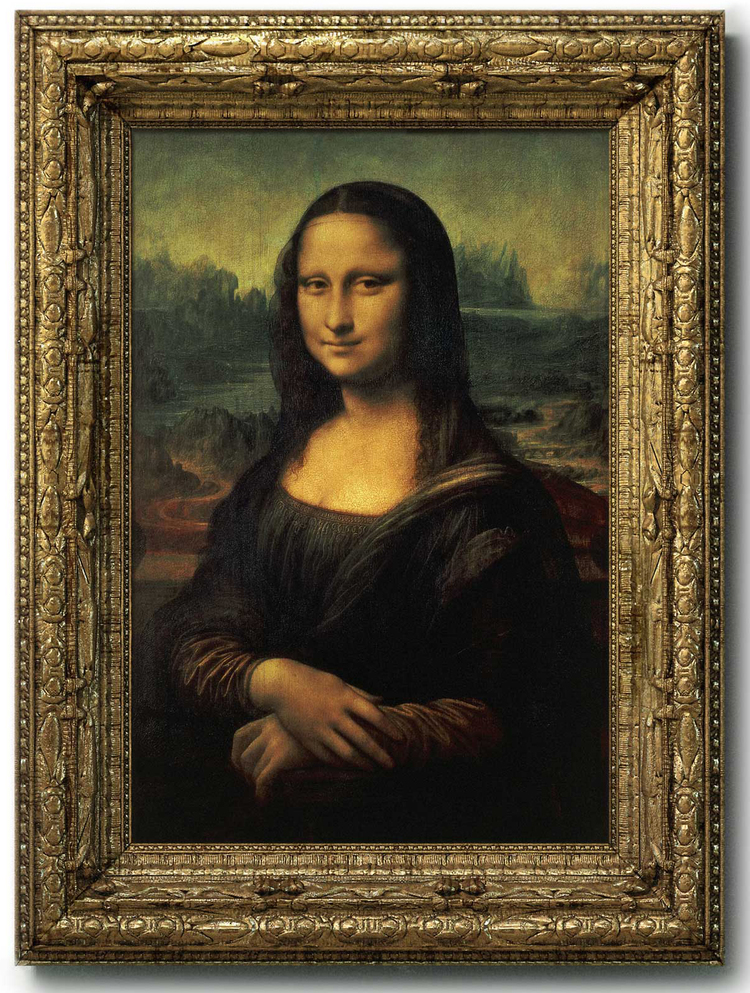

Is the most famous work of art in existence. Her face is also one of the most recognizable - and is potentially worth a billion dollars. It's both a mystery and a controversy over who she really is and how she was painted.

The Mona Lisa: Quick Facts & Notes

Dimensions: 30 × 21 inches (77 × 53.2 cm)

The panel itself is slightly larger: 79.4 × 53.4 × 1.4 cm. Due to aging, the width has shrunk from its original 55.5 cm to 53.2 cm.Medium: Painted on poplar wood.

Timeline:

Initially painted between 1503–1507, though recent research extends this timeline to 1503–1519—Leonardo likely worked on her until his death.Hidden Layers: X-rays reveal at least three other paintings or layers underneath the visible surface, suggesting the painting evolved significantly over time.

Ownership: The painting is owned by the French government and housed in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

The Name Debate

The Mona Lisa wasn’t always called by her famous name. It wasn’t until after Leonardo’s death that she became known as "Mona Lisa." Before that, she was referred to by different names:

“A Courtesan in a Gauze Veil”: (Unlikely, as Lisa Gherardini wasn’t a courtesan.)

“A Certain Florentine Lady”: Raises questions—if they knew the model, why such a vague title?

“La Gioconda” or “La Joconde”: Translates to "Light-Hearted Woman," a reference to Lisa Gherardini’s married name (Giaconda).

Her veil—a Guarnello—was a traditional garment worn by pregnant women of the time, adding another layer of mystery.

Pillars: Were They Removed?

Early copies of the Mona Lisa show pillars flanking the composition, with visible bases still present in the original. This raises questions:

Were the sides of the painting cropped at some point, removing the pillars?

Or were the pillars an element added in later copies, not part of Leonardo’s original work?

Even without the pillars, their remnants and the debate around them add another layer to the painting’s enigmatic history.

The Mystery of the Mona Lisa: Leonardo’s Self-Portrait and Other Secrets

Leonardo’s Hidden Self-Portrait

In 1987, artist and researcher Lillian Schwartz noticed a fascinating connection: the face of the Mona Lisa aligns remarkably well with Leonardo da Vinci’s self-portrait. When I tested this myself, I found she was right. The alignment is too precise to be coincidental, suggesting that Leonardo intentionally incorporated elements of his own face into the Mona Lisa. But why? Could it be an act of self-reflection, a clever signature, or perhaps something deeper?

The Case of the Missing Eyebrows

One of the most debated aspects of the Mona Lisa is her lack of visible eyebrows. In 2007, French engineer Pascal Cotte analyzed the painting using multispectral scanning and declared:

"One day I said, if I can find only one hair, only one hair of the eyebrow, I will have definitive proof that originally Leonardo had painted eyelashes and eyebrows."

This suggests that the eyebrows were once there but may have been removed during restoration, faded over time, or were deliberately left obscure by Leonardo to enhance his sfumato effect. Another theory is that he omitted the eyebrows intentionally to create a softer, more enigmatic expression.

Who Is the Mona Lisa?

The mystery of the Mona Lisa deepens when we ask: Who is she? In 2005, researchers at Heidelberg University discovered notes from 1503 that mention Leonardo was working "on the head of Lisa del Giocondo." While this supports the theory that the Mona Lisa depicts Lisa Gherardini, that doesn’t necessarily mean the version we see today is her final likeness.

Over nearly 20 years of work, Leonardo added thousands of ultra-thin paint layers to the Mona Lisa. This long process could mean that her image evolved significantly over time, possibly starting as Lisa Gherardini and ending as a blend of multiple influences—or even something entirely different.

Priceless and Perceptual

The Mona Lisa once held the Guinness World Record for the most expensive painting, valued at $100 million in 1962—equivalent to nearly $1 billion today when adjusted for inflation. But today, she is considered "priceless" and is no longer insurable, as her cultural and historical significance transcends monetary value.

Her expression, however, might be her greatest enigma. The sfumato technique, which blurs the boundaries of light and shadow, creates a perceptual illusion that makes her expression change depending on the viewer’s perception. Some see a smile, others a smirk, and still others an entirely different emotion. For me, her expression seems to say, "I know something you don’t know."

This psychological effect taps into our expectations and biases, making the Mona Lisa not just a portrait but an interactive experience. It’s an optical illusion of light and emotion, one that truly needs to be seen in person to appreciate its full complexity.

Layers of Mystery

Ultimately, the Mona Lisa is more than just a painting; she is a puzzle, a mirror, and a masterpiece all in one. From the possibility of Leonardo’s hidden self-portrait to her enigmatic expression, the secrets of the Mona Lisa continue to fascinate and inspire, just as Leonardo intended.

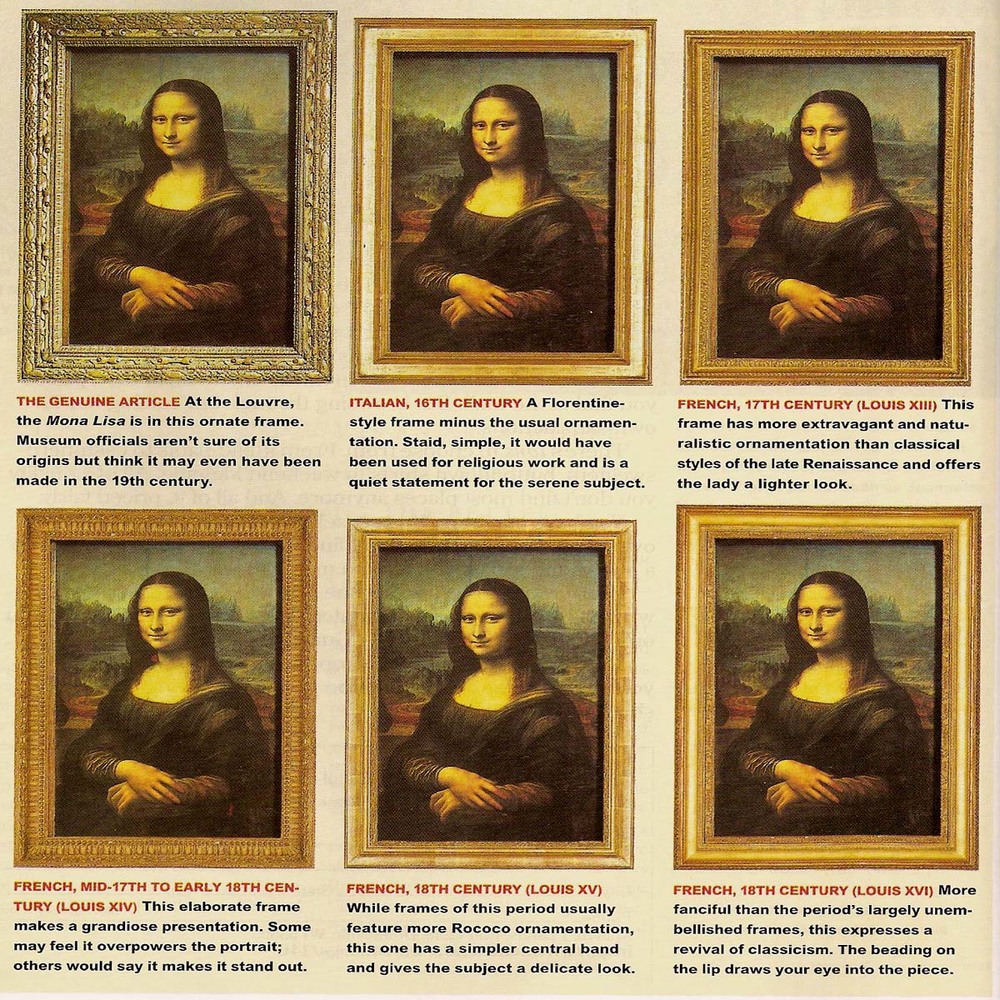

Copy by - unknown. Notice the blacked out background and the presence of the pillars

The Painting

The Mona Lisa—the most famous work of art in the world. Worth over a billion dollars, this masterpiece was painted by the greatest genius of all time, Leonardo da Vinci. She consists of hundreds of thousands of paint layers, each thinner than a human hair. Even with the use of advanced 3D laser scanning technology, we still cannot fully understand how she was painted—500 years ago.

Her fame transcends the art world. Britney Spears wrote a song about her. Countless rappers have referenced her. She’s been featured in movies, documentaries, articles, papers, and books. But the question remains: Why is this painting so special?

"The best and most powerful way to explain why the Mona Lisa is considered the greatest painting of all time would be to hand you a brush and ask you to paint her yourself."

— Discovering Da Vinci's Daughter

Why would someone who is considered the smartest person in history, the greatest artist who ever lived, dedicate 20+ years to a single painting? This is a man who invented airplanes, rail-guns, tanks, automobiles, parachutes, helicopters, and scuba gear—centuries ahead of his time. Why did the Mona Lisa command such devotion?

There’s a reason for her complexity. There’s a reason she’s the most famous face in the world. She was designed to be—and Leonardo succeeded beyond imagination.

A Mystery Designed to Last

Who she is, when she was painted, and how she was painted—these remain some of the art world’s greatest mysteries. But why? Why are there so many unanswered questions about a painting by someone who documented almost everything?

In Leonardo’s thousands of notebook pages, there is no direct mention of the Mona Lisa. He didn’t even give her a title. Instead, his journals seem to guide us toward truly seeing her. Once you can do that, the mysteries of the Mona Lisa turn from coincidences to clues—a puzzle waiting to be unraveled.

"George Dawe was an English portrait artist who painted 329 portraits of Russian generals active during Napoleon's invasion of Russia for the Military Gallery of the Winter Palace, Saint Petersburg, Russia. I'm using digital copies of these paintings as a basis for my own work which involves incorporating celebrities into the paintings using photoshop." Link

Above demonstrates the idea that I'm going to describe. The "Mona Lisa' wasn't just a portrait of a individual woman "Lisa" it was a style/ pose/ composition/ position/ that became a "Mona Pose" or technically a "Portrait style" - like the example above, Leonardo would use the composition as a type of template to paint multiple people and to teach others. Similar to a standard paint by numbers. Another way to think about it would be to get your face on a coin or a dollar bill except the pose was not the portrait of Lisa G, it was getting yourself done in a Giacondo or a "Mona Lisa" in the same way that we use terms like Windex/ instead of window cleaner. Instead of saying "portrait" "Mona Lisa" became synonymous with getting your portrait done in THAT STYLE. Just like how "Selfie" became synonymous with "Self portrait"

Copy of a Copy of a Copy…

Why would anyone create multiple versions of a portrait from a copy? It’s like using a copy machine—each duplication loses a bit of the original’s precision. With each iteration, the image drifts further from the source. If the Mona Lisa we see today started as a portrait of a real-life Lisa Gherardini, then the versions, copies, and especially the final Mona Lisa in the Louvre have evolved far beyond their origins.

Even in the surviving copies, you’ll notice that while the pose remains consistent, the faces are not identical—they aren’t even the same person. How could they be, with 10+ years of development and thousands of ultra-thin paint layers involved? If the original portrait and the final painting shared the same piece of poplar wood, it’s almost certain that the image we see today is the result of transformation rather than preservation.

Over the course of about 20 years, Leonardo refined and reworked the "Mona Lisa pose/composition" not just for this painting but as a teaching tool for his students. Numerous copies were created during his lifetime by his followers, and the same pose became a new stylistic standard for other painters of the era. It was a “thing” back then—just like it is now—to commission your portrait in the iconic “Mona Pose.”

It’s entirely possible that the real-life Lisa Gherardini was just one of many sitters, or perhaps not even the first. She certainly wasn’t the last. The Mona Lisa we revere today could be more than a simple portrait; it’s likely an evolving masterpiece that combines multiple influences, layers of experimentation, and Leonardo’s pursuit of perfection.

Symbolism and Evolution: The Layers of the Mona Lisa

The Mona Lisa, like many of Leonardo’s works, wasn’t just a portrait—it was a deeply symbolic piece, evolving with layers of meaning. Much like today’s caricatures with personal touches, the painting reflected symbolic elements unique to its subject. For example, in one early version, the sitter is shown holding a reed or plant, potentially symbolizing her connection to the textile trade. Similarly, Lady with an Ermine uses the animal as a symbol of status and virtue. As Leonardo reworked the Mona Lisa, it became something more personal, a reflection of his artistic legacy, diverging from its initial intent.

The Painting in Three Parts

To truly understand the Mona Lisa, it helps to break the painting into three distinct components:

The Composition

This refers to the arrangement of the painting: the sitter on a ledge, overlooking a dreamlike landscape with rivers, rocks, and a disjointed perspective. These elements form the painting’s structural framework.The Sitter (The Pose)

The iconic pose—a woman seated with her hands folded—is as recognizable as the painting itself. It became a template for countless portraits, both in Leonardo’s time and beyond, immortalizing the pose rather than the individual.The Face

The face represents the sitter’s identity—or does it? Across multiple versions attributed to Leonardo or his students, the faces vary significantly. While the pose and composition remain constant, the facial features shift, raising the question: was this even the same person? Or was the face a construct, layered and refined over time?

A Journey Through Versions

Even during Leonardo’s lifetime, there were multiple iterations of the Mona Lisa. The "Proto Mona" or cartoon sketch shows the foundational pose. The Isleworth Mona Lisa introduced the same pose with a background, but the face appears different. The Prado Mona Lisa, likely painted alongside the "original," mirrors its composition so precisely that it must have been copied intentionally, yet the faces differ. Finally, the Louvre Mona Lisa—the most famous version—evolved into the enigmatic masterpiece we know today.

A Timeline of Complexity

These versions span nearly two decades, with gaps of years between their creation. How could all these paintings have been based on a live sitter? The answer is simple—they weren’t. Instead, Leonardo used the Mona Lisa as a testing ground for technique and as a teaching tool for his students, many of whom created their own versions. It’s unlikely the Louvre Mona Lisa was painted from life at all, but rather became the culmination of an idea—an evolution of artistry and symbolism rather than a straightforward portrait.

The Legacy of an Idea

The Mona Lisa we see today is far more than a depiction of a woman named Lisa Gherardini. It’s a layered masterpiece, born from decades of experimentation, personal meaning, and artistic innovation. It transcends its origin, blending reality and imagination, and stands as a testament to Leonardo’s enduring genius.

The Evolution of the Mona Lisa: From Isleworth to Prado to Louvre

The journey from the Isleworth Mona Lisa to the Prado and finally to the Louvre version is less a smooth evolution and more a dramatic revolution of artistic intent and execution. Here's why:

From Isleworth to Prado: A Leap in Vision

The Isleworth Mona Lisa appears simpler in its execution, serving as an early exploration of the pose and composition. By the time of the Prado Mona Lisa, the work underwent significant changes: a more developed background, refined details, and greater attention to sfumato. These differences suggest a deliberate reimagining rather than a gradual refinement.From Prado to Louvre: Identical Compositions

The similarities between the Prado and Louvre Mona Lisa are so striking that they cannot be coincidental. The compositions align almost perfectly, indicating that both were based on the same underlying framework. These were not two artists working independently from life; instead, they were likely following a predefined template or “blueprint.”Collaboration and Methodology

The Prado Mona Lisa is thought to have been painted by Salai, Leonardo’s pupil and companion, while the Louvre Mona Lisa was completed by Leonardo himself. The underdrawings and compositional elements in both works reveal a shared origin, suggesting the two painters worked side by side or under the same meticulous guidance. This collaborative process implies that Leonardo and Salai were deliberately creating parallel versions, starting from a common design and filling them in with their respective touches.A "Paint-by-Numbers" Foundation

The method used in these works may have resembled a structured "paint-by-numbers" approach, where the foundational composition—pose, proportions, and background—was established first. This would allow for consistency across versions while giving room for individual interpretation and refinement in details, such as sfumato or color blending.

Why This Matters

This discovery underscores the depth of Leonardo’s teaching and his methods of experimentation. By producing nearly identical compositions with subtle variations, Leonardo was not only creating a masterpiece but also training his students and testing his own theories on art and perception. It also reinforces the notion that the Mona Lisa was more than a simple portrait; it was a template, a study, and a legacy in itself.

The Mona Lisa we know today—the Louvre version—is the culmination of this collaborative and iterative process. It embodies the highest refinement of Leonardo’s vision, while its sister versions offer a glimpse into the steps that led to its creation.

The Composition

The Composition

The composition of the Mona Lisa is a masterclass in arrangement and balance. The painting depicts a woman seated on a ledge, flanked by what appear to be remnants of columns, overlooking a dreamlike, disjointed landscape. This background features clouds, jagged rocks, rivers, and a distant bridge, all contributing to the painting’s ethereal atmosphere. The careful placement of these elements creates a harmonious yet subtly unsettling scene. If outlined, the composition reveals its mathematical precision and the deliberate use of perspective to guide the viewer’s gaze.

The Sitter: The Iconic Pose

The sitter’s pose is one of the most recognizable aspects of the Mona Lisa. While her identity is debated, her seated position—with her hands gracefully crossed in front of her, draped in timeless clothing—has become iconic. This pose exudes poise and serenity, yet it is also inviting and enigmatic. It’s a pose that has been endlessly imitated, from historical portraits to modern parodies, further solidifying her as a universal symbol of mystery and artistry.

Her understated expression and composed posture are part of what makes the painting timeless, transcending its era to remain relevant in today’s visual culture.

The Face

This means how her actual face appears. Her facial structure, skin tone, etc. That you would recognize her by her face alone.

Why the perspective unexpectedly rises behind the sitter.

The Curious Case of the Mona Lisa’s Perspective

When the Mona Lisa is rolled into a cylinder so that the outer edges touch, something extraordinary happens—the edges of the perspective align perfectly. This discovery highlights an intentional design choice by Leonardo da Vinci, who mastered the rules of perspective and certainly did not make such an "error" by accident.

The Perspective Mystery

The background of the Mona Lisa is strikingly asymmetrical. The landscape on her right side appears to sit higher than that on her left, creating a perceptual dissonance. Why would Leonardo, a pioneer of perspective, create such an anomaly? This "mistake" seems to be a deliberate feature, designed to engage the viewer’s subconscious mind.

Rolling the Painting: A Hidden Effect

When the painting’s outer edges are curved to meet, the perspective realigns, resolving the apparent asymmetry. This effect suggests that the composition was meticulously designed with an optical illusion in mind. The subconscious re-alignment of the misaligned edges creates a dynamic sense of depth and movement, adding an almost cinematic quality to the painting.

The Missing Pillars: A Clue

The Mona Lisa originally featured pillars on either side of the composition, visible in early copies and through remnants on the edges of the painting. These were likely removed at some point, either by design or during framing. Their absence opens up the painting, amplifying the mysterious interplay of perspective.

The removal of the pillars makes it possible to perform the "rolling alignment" demonstration. This transformation invites viewers to ask, "Why were the sides removed?" and "What is Leonardo trying to convey?" It turns a seemingly straightforward portrait into a layered puzzle, encouraging further exploration.

Leonardo’s Optical Illusion

Leonardo was not only an artist but also an inventor and master of visual tricks. The misaligned perspective is likely a deliberate "special effect," adding subtle movement and engaging the viewer’s visual processing. This ingenious technique transforms the painting into an interactive experience, proving once again that the Mona Lisa is more than just a portrait—it’s a masterful experiment in perception and design.

The Columns

The Mystery of the Columns in the Mona Lisa

The Mona Lisa features remnants of columns on either side of the ledge or window where she sits. This intriguing detail has sparked debate: Were the sides of the painting originally cut down, or were the columns added later—perhaps even by someone other than Leonardo?

Evidence from the Painting’s Edges

In the Mona Lisa (Louvre Version) without its frame, the paint ends before the wood does. This indicates that if the edges were cut down, no part of the original painted image was removed. The consistency of the unfinished edges at the corners and top suggests that the current composition was always intended to end where it does.

The Columns: Added Later?

A closer look reveals that the columns appear somewhat transparent, allowing the ledge to be visible through them. This transparency indicates that the columns might have been added later, painted over the existing structure. If true, this would align with the idea that they were not part of Leonardo’s original design but a later addition by another artist or during restoration.

Earlier Versions with Defined Columns

In earlier versions of the Mona Lisa—such as the Isleworth Mona Lisa—the columns are more prominent and take up significant space. These versions suggest that the columned composition might have been part of a common motif for portraits in Leonardo’s workshop or during that period. However, their subtler presence in the Louvre version adds to the painting's air of mystery.

The Columns and Perspective

The inclusion or removal of columns plays into the painting’s overall composition and optical illusions. If they were removed, their absence could enhance the Mona Lisa’s enigmatic quality by focusing attention solely on her gaze and the surreal landscape.

Ultimately, the question of the columns—whether they were removed, added, or altered—only deepens the enigma surrounding Leonardo’s masterpiece. Their presence or absence, much like the painting itself, seems designed to invite interpretation and spark curiosity.

"Kenneth Clark, in his letter to Murray Urquhart of 25th February, 1943, opines that columns evidently formed part of the original design (of the Louvre ‘Mona Lisa’).

In 1959, the distinguished German art historian, Richard Friedenthal: (‘Leonardo da Vinci – A Pictorial Biography’) states that “ … it [the Louvre ‘Mona Lisa’] was cut by about 10cm on each side.” That would have meant that the panel was wider by about 20cm, roughly 8 inches.

“The lady sits by the parapet of a loggia, which was originally extended at each side to include two columns framing the landscape, as in a window. These are now reduced to little more than vertical strips, but their bases are easily visible and their foreshortening offers the only element of linear perspective in the picture. Originally, then, the overwhelming presence of the lady was kept in check by the architectural structure of her setting.” (Carlo Pedretti: ’Leonardo – A Study in Chronology and Style’, 1973)

Professor Pedretti here makes the strong point that the architectural structure of the Louvre version of the ‘Mona Lisa’ would have been better served with columns to frame the composition. Leonardo’s ‘Earlier Version’ has columns that can be clearly seen in their original state.

In ‘Leonardo – The Artist and the Man’ (English edition, 1992), Serge Bramly writes: “The panel has lost a strip of about seven centimeters from each side: we can no longer see the two columns that originally framed the landscape, which appear in old copies and in Raphael’s drawing.”

In a subsequent book: ‘Mona Lisa – The Enigma’, author Bramly iterates: “Like so many of Leonardo’s works, the ‘Mona Lisa’ has suffered both from the ravages of time and from rough treatment by restorers: it has been narrowed by six or seven centimeters on both the right and left.”

Professor Pietro Marani, (in ‘Leonardo da Vinci – The Complete Paintings’, 2000) writes: “She does sit between two columns that, because the panel has been cut down at the sides, are now scarcely visible at the very edges of the composition.”

In ‘Art In Renaissance Italy’ by John T. Paoletti and Gary M. Radke, the authors write in 2005 that: “At one time the figure was flanked by columns whose bases are part visible on the ledge behind her …” "

Quotes compiled by monalisa.org

Who Was the Model?

The Identity Puzzle

The mystery of the Mona Lisa’s sitter arises from conflicting historical accounts and the ambiguity of Leonardo da Vinci’s own records. There are multiple paintings and versions attributed to Leonardo and his workshop, making it challenging to pinpoint which specific painting or individual is being referenced. Without concrete details—such as those present in Lady with an Ermine—the Mona Lisa remains a puzzle of “Who is she?”

Traditional Attribution: Lisa Gherardini

The most widely accepted theory is that the sitter was Lisa Gherardini, the wife of wealthy Florentine silk merchant Francesco del Giocondo. This attribution stems from a single sentence by Leonardo’s biographer, Giorgio Vasari, who wrote 30 years after Leonardo’s death:

“Leonardo undertook to execute, for Francesco del Giocondo, the portrait of Mona Lisa, his wife; and after toiling over it for four years, he left it unfinished; and the work is now in the collection of King Francis of France, at Fontainebleau.” – Vasari

However, Vasari never met Leonardo, and his claim has been contested.

Another Account: Antonio de Beatis

In 1517, Antonio de Beatis, a secretary visiting Leonardo, noted that he was working on a portrait of "a certain Florentine woman” commissioned by Giuliano de’ Medici. This conflicts with Vasari's account, introducing uncertainty about whether Lisa Gherardini was indeed the model or if Leonardo painted multiple portraits over the years.

Conflicting Titles

Before being called the Mona Lisa, the painting went by various names:

“A Certain Florentine Lady”

“A Courtesan in a Gauze Veil”

“La Joconde” (French for “light-hearted”)

“La Gioconda” (Italian for “light-hearted woman”)

The French title La Joconde and the Italian La Gioconda seem to play on Francesco del Giocondo’s last name and the sitter’s enigmatic smile, creating a web of wordplay and coincidences.

Coincidences and Wordplay

The names associated with the painting create an intricate puzzle:

La Joconde translates to light-hearted, describing her expression.

Francesco del Giocondo’s surname, Giocondo, also means light-hearted in Italian.

The heart of the painting—her chest area—is literally the brightest and central point of the composition.

Did Leonardo choose Lisa Gherardini as a model because of her husband’s name? Or was her identity secondary to the symbolism and the wordplay surrounding her expression and pose?

The Evolution of the Painting

Given the painting’s nearly 20-year development and Leonardo’s penchant for experimentation:

It’s likely the painting evolved beyond a simple portrait of Lisa Gherardini.

Leonardo’s use of thousands of translucent layers and his focus on universal beauty suggest he may have blended multiple influences or even created an idealized figure.

This leads to the possibility that the Mona Lisa is less about one woman and more about an abstract, symbolic vision of humanity, emotion, and genius.

Light-Hearted Mystery

The combination of titles, linguistic coincidences, and subtle details in the painting point to a deliberate layering of meanings. The Mona Lisa isn’t just a portrait—it’s a puzzle that invites viewers to explore, question, and interpret, just as Leonardo intended. Whether Lisa Gherardini was the true sitter or merely a starting point, her identity has become a part of the painting’s enduring mystique.

Timeline

The Mona Lisa, painted by Leonardo da Vinci, is renowned for its enigmatic smile and the mystery surrounding the sitter's identity. Believed to be Lisa Gherardini, the wife of Florentine merchant Francesco del Giocondo, the painting's history is rich and complex. Below is a timeline highlighting key events in the Mona Lisa's journey:

1452: Leonardo da Vinci is born in Anchiano, near Vinci, Italy.

1479: Lisa Gherardini, later known as Mona Lisa del Giocondo, is born in Florence.

1500: Leonardo returns to Florence from Milan, marking a period of prolific artistic creation.

1503: Leonardo begins painting the portrait of Lisa Gherardini, commissioned by her husband, Francesco del Giocondo. citeturn0search2

1503: Agostino Vespucci notes Leonardo's work on Lisa Gherardini's portrait, suggesting it may remain unfinished. citeturn0search2

1504: Artist Raphael creates a pen-and-ink sketch based on Leonardo's portrait, indicating the Mona Lisa's influence on contemporaneous artists. citeturn0search12

1506: After approximately four years, Leonardo leaves the painting unfinished, a common practice in his oeuvre. citeturn0search12

1513-1516: Leonardo works under the patronage of Giuliano de' Medici in Rome, possibly continuing to refine the Mona Lisa during this period. citeturn0search12

1516: Invited by King Francis I, Leonardo moves to France, bringing the Mona Lisa with him. citeturn0search12

1517: Antonio de Beatis records a visit where Leonardo shows a portrait of "a certain Florentine lady," believed to be the Mona Lisa. citeturn0search12

1519: Leonardo da Vinci passes away in France; the Mona Lisa is acquired by King Francis I and placed in the Palace of Fontainebleau. citeturn0search12

1797: Following the French Revolution, the painting is moved to the Louvre Museum in Paris, where it remains on permanent display. citeturn0search12

1911: On August 21, the Mona Lisa is stolen by Vincenzo Peruggia, an Italian patriot who believes the painting should be returned to Italy. It is recovered in 1913. citeturn0search12

1956: The painting suffers two attacks: once with acid and another time when a rock is thrown at it, leading to the installation of protective glass. citeturn0search12

1962-1963: The Mona Lisa is exhibited in the United States, drawing over a million visitors in Washington, D.C., and New York City. citeturn0search10

1974: The painting is displayed in Tokyo and Moscow, continuing its international exhibitions. citeturn0search12

2005: A new protective glass case is installed to shield the painting from potential vandalism and environmental damage. citeturn0search12

2022: In May, an activist throws cake at the protective glass covering the painting in an attempt to raise awareness for climate change; the painting remains unharmed. citeturn0search12

This timeline encapsulates the Mona Lisa's storied past, reflecting its enduring significance and the fascination it continues to evoke worldwide.

The Isleworth Mona Lisa

The History of the Mona Lisa

The story behind the Mona Lisa is as enigmatic as her smile. Despite being created by one of history’s most meticulous record-keepers, Leonardo da Vinci left us with no title, date, or direct mention of this painting in his extensive journals. Everything we "know" about the Mona Lisa—her identity, history, and even her name—comes from secondary sources like Giorgio Vasari, Leonardo's first biographer, who wrote decades after Leonardo’s death.

Vasari claimed that Leonardo worked on the portrait for four years and carried it with him until his death in 1519. At some point, the painting made its way into the hands of King François I of France, who either purchased it or inherited it after Leonardo’s passing. Since then, the Mona Lisa has remained in France, where it resides today in the Louvre Museum.

Yet questions persist: Why didn’t Leonardo leave any concrete documentation about this painting? Could the lack of information be intentional, adding to the mystique? And how did the Mona Lisa transition from being an admired Renaissance portrait to the most famous painting in the world?

The Rise of Her Fame

Before the advent of photography, the Mona Lisa’s fame was confined to those who could see her in person—mainly art aficionados and scholars. It wasn’t until the painting was stolen in 1911 that she gained widespread recognition. Her absence sparked global headlines, and her recovery two years later solidified her as a cultural icon. Her mystique grew with time, fueled by her enigmatic smile, the innovations of Leonardo’s sfumato technique, and the enduring mystery of her identity.

The Mona Lisa’s complexity makes her nearly impossible to replicate convincingly. This, combined with her intriguing history and Leonardo’s reputation, has elevated her to unparalleled cultural status.

What Others Have to Say About the Mona Lisa

The Mona Lisa has captivated artists, thinkers, and critics for centuries, inspiring reflections that range from poetic to philosophical. Her enigmatic smile, her haunting gaze, and the mysteries surrounding her creation have evoked some of the most profound and evocative statements about art, beauty, and genius.

Walter Pater (1873):

“She is older than the rocks among which she sits; like the vampire, she has been dead many times and learned the secrets of the grave.”

In his Studies in the History of the Renaissance, Pater compares the Mona Lisa to an eternal being, suggesting that her beauty transcends time and mortality. Her presence feels ancient yet ageless, filled with secrets and wisdom.

André Salmon (1912):

“The smile of La Gioconda (another title for Mona Lisa) was for too long, perhaps, the Sun of Art. The adoration of her is like a decadent Christianity—peculiarly depressing, utterly demoralizing. One might say, to paraphrase Arthur Rimbaud, that La Gioconda, the eternal Gioconda, has been a thief of the energies.”

Salmon critiques the almost religious devotion to the Mona Lisa, likening her allure to an oppressive force. He hints that her fame has overshadowed other masterpieces, creating an almost cult-like obsession.

George Moore (1914):

“Her hesitating smile which held my youth in a little tether has come to seem to me but a grimace and the pale mountains no more mysterious than a globe or map seen at a distance… a sort of riddle, an acrostic, a poetical decoction.”

For Moore, the Mona Lisa embodies an intellectual puzzle—less a painting than a literary work. Her beauty and mystery are woven into a tapestry of riddles and symbols, challenging viewers to decipher her meaning.

Will Rogers:

“Mona Lisa is the only beauty who went through history and retained her reputation.”

Rogers underscores her unparalleled legacy, highlighting how the Mona Lisa’s allure has endured the scrutiny of centuries, a testament to her timeless appeal.

William F. Buckley:

“How could we possibly appreciate the Mona Lisa if Leonardo had written at the bottom of the canvas: 'The lady is smiling because she is hiding a secret from her lover.' This would shackle the viewer to reality, and I don't want this to happen to 2001.”

Buckley reflects on the power of ambiguity, suggesting that the lack of definitive explanation enhances the Mona Lisa’s mystique. The open-ended nature of her smile leaves room for infinite interpretations.

Alfred Whitney Griswold (1958):

“Could Hamlet have been written by a committee, or the Mona Lisa painted by a club? Creative ideas do not spring from groups. They spring from individuals. The divine spark leaps from the finger of God to the finger of Adam.”

Griswold celebrates the individual genius of Leonardo da Vinci, emphasizing that such timeless creations arise from singular, inspired minds rather than collaborative efforts.

Théophile Gautier (1859):

"The Mona Lisa is a kind of marble idol with her hands crossed like an Egyptian statue. She seems to command the elements, and one almost expects her to rise and walk on the clouds."

Gautier paints a poetic picture of the Mona Lisa as a goddess-like figure, imbued with an almost supernatural power and serenity.

Sigmund Freud (1910):

“The smile that plays so enigmatically on her lips charms men as a promise of some secret satisfaction that is forever denied.”

Freud famously interpreted the Mona Lisa as a representation of Leonardo’s unresolved maternal feelings, suggesting that her smile reflects subconscious longing and mystery.

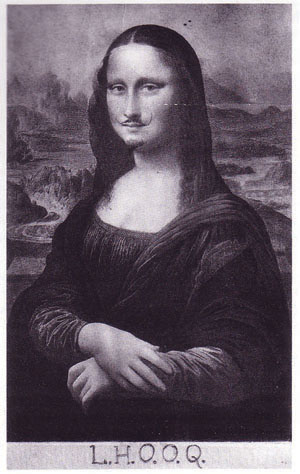

Marcel Duchamp:

By defacing her with a mustache and the letters "L.H.O.O.Q." (a pun translating roughly to "She has a hot ass"), Duchamp both parodied and paid homage to the Mona Lisa, challenging traditional notions of art and beauty while underscoring her iconic status.

Vladimir Nabokov (1951):

“The infinite power of the Mona Lisa's expression is the mirror in which every visitor to the Louvre beholds his or her own emotions reflected."

Nabokov highlights the Mona Lisa’s ability to connect personally with each viewer, serving as a canvas for individual interpretation.

The Mona Lisa has inspired awe, critique, and even playful irreverence, but one thing remains clear: her legacy endures because she defies easy explanation. Whether viewed as a symbol of perfection, an intellectual puzzle, or a cultural phenomenon, she continues to provoke thought and captivate imagination across generations.

Certainly, here are additional reflections on the Mona Lisa that highlight her enduring allure and the diverse interpretations she inspires:

Salvador Dalí:

"Mona Lisa has no eyebrows. I wonder what happened to them."

Dalí humorously points out a curious detail, sparking discussions about Leonardo's techniques and the painting's history. citeturn0search1

Bob Dylan:

"Mona Lisa must have had the highway blues; you can tell by the way she smiles."

Dylan poetically suggests that her enigmatic smile hints at hidden stories or emotions. citeturn0search0

Louis Armstrong:

"A lotta cats copy the Mona Lisa, but people still line up to see the original."

Armstrong emphasizes the irreplaceable value of the original masterpiece, despite numerous reproductions. citeturn0search0

Chuck Palahniuk:

"Hey, even the Mona Lisa is falling apart."

Palahniuk uses the painting as a metaphor for decay, perhaps commenting on the impermanence of art and life. citeturn0search0

Dave Barry:

"You should definitely visit the Louvre, a world-famous art museum where you can view, at close range, the backs of thousands of other tourists trying to see the Mona Lisa."

Barry humorously critiques the crowded experience of viewing the painting, highlighting its immense popularity. citeturn0search0

Stephanie Perkins:

"If I had a euro for every stupid thing I’ve done, I could buy the Mona Lisa."

Perkins uses the painting's immense value as a humorous benchmark for personal mistakes. citeturn0search6

Jerry Seinfeld:

"The Mona Lisa is the world’s most overrated painting. It’s just a portrait of some Italian lady who probably had bad breath."

Seinfeld offers a tongue-in-cheek critique, challenging the universal adoration of the artwork. citeturn0search6

Paulo Coelho:

"With all due respect, the Mona Lisa is overrated."

Coelho provocatively questions the painting's legendary status, inviting reflection on subjective perceptions of art. citeturn0search6

These perspectives showcase the Mona Lisa's profound impact on culture, inspiring admiration, critique, humor, and contemplation across various fields and eras.

Articles

This story does not 'confirm' Mona's identity all it does is give evidence that Leonardo had painted, or started a painting/ portrait of Lisa. That does not mean the painting or the person in the painting was/ is her. This could, and is probably referring to the earlier copy (The Isleworth) or even an unknown or lost version. It's also only an additional source that states the same as Vassari had.

Mona Lisa's Identity Confirmed by Document

Rossella Lorenzi, Discovery News

Mona Lisa Is Lisa

Notes written in October 1503 in the margin of a book held at Heidelberg University Library confirm Mona Lisa's identity as Lisa Gherardini del Giocondo.

Courtesy of Giuseppe Pallanti |

Birth Certificate

Lisa Gherardini was born on June 15, 1479 in Florence, as birth certificate states, shown here. She was born in a dark alley known as Via Sguazza. The house stood a few hundred feet from the bridge Ponte Vecchio. Rain water and sewage stagnated just in front of the house -- hence the name "sguazza†-- meaning swash.

Jan. 16, 2008 -- The mystery over the identity of the woman behind Leonardo da Vinci's "Mona Lisa" painting has been solved once and for all, German academics at Heidelberg University announced on Tuesday.

Mona Lisa is "undoubtedly" Lisa Gherardini del Giocondo, according to Veit Probst, director of the Heidelberg University Library.

Conclusive evidence came from notes written in October 1503 in the margin of a book.

Discovered two years ago in the library's collection by manuscript expert Armin Schlechter, the notes were made by Florentine city official Agostino Vespucci, an acquaintance of Leonardo da Vinci, in an edition of letters by the Roman orator, Cicero.

In his annotations, Vespucci wrote that Leonardo was working on three paintings at the time, including a portrait of Lisa del Giocondo.

"All doubts about the identity of the 'Mona Lisa' have been eliminated," the university said in a statement.

Vespucci's notes also "establish more precisely the year the painting was done," the university said.

Until now, the only other source to have identified the sitter in Leonardo's masterpiece as Lisa Gherardini, was the 16th century painter and art historian Giorgio Vasari.

In his work "Lives of the Artists," Vasari named Lisa Gherardini, the wife of the wealthy Florentine silk merchant Francesco del Giocondo as the subject of the portrait and concluded that the portrait was painted between 1503 and 1506.

But doubts about Vasari's attribution have always abounded since he was known to rely on anecdotal evidence.

The work is unsigned, undated and bears nothing to indicate the sitter's name. Attempts to solve the mystery surrounding her famous smile as well as her identity have included theories that she was the artist's mother, a noblewoman, a courtesan, even a prostitute.

There have also been theories that the sitter was happily pregnant, or affected by various diseases ranging from facial paralysis to the compulsive gnashing of teeth.

"The German finding confirms that Vasari is indeed a reliable source," Giuseppe Pallanti, the author of two books on the "Mona Lisa," told Discovery News.

Pallanti was the first historian to identify the sitter in Leonardo's portrait as Lisa Gherardini, following 25 years of research.

"Indeed, I found documents showing that Leonardo's father -- a local notary, Ser Piero da Vinci -- and Lisa's family were neighbors, living about 10 feet away from each other in Via Ghibellina," Pallanti said. "Leonardo met a pregnant Lisa in 1500 in Florence. In December 1502 she gave birth again."

According to Pallanti’s research, Lisa Gherardini, a member of a minor noble family of rural origins, was born on June 15, 1479, in a rather ugly house in Via Sguazza in Florence.

In 1495, when she was 16 years old, she married the merchant Francesco del Giocondo. Ser Francesco was 14 years her senior and had lost his first wife, Camilla Rucellai, the previous year.

The girl moved to Del Giocondo's house, located in today's San Lorenzo market quarter. Though the house was big and beautiful, the surroundings were less than ideal. Prostitutes populated the area, which was a sort of Renaissance red light district.

In that house, Lisa gave birth to five children: Piero, Andrea, Giocondo, Camilla and Marietta.

Pallanti was also able to reconstruct Lisa's last years. She died four years after her husband's death on July 15, 1542, at age 63, and was buried in the convent Saint Orsola."

Frequently Asked Questions About the Mona Lisa

1. Why is the Mona Lisa so famous?

The Mona Lisa is renowned for her enigmatic smile, lifelike realism, and the mastery of Leonardo da Vinci’s sfumato technique. She has become a cultural icon, referenced in countless works of art, literature, and popular culture.

2. Who is the Mona Lisa?

The Mona Lisa is widely believed to be Lisa Gherardini, the wife of Florentine merchant Francesco del Giocondo. However, theories suggest she might represent an idealized woman, a composite of multiple faces, or even a disguised self-portrait of Leonardo.

3. How long did it take to paint the Mona Lisa?

Leonardo worked on the Mona Lisa intermittently between 1503 and 1519. He continued refining it until his death, making it a lifelong project.

4. Why is the Mona Lisa not for sale?

The Mona Lisa is considered priceless and is owned by the French government. It is housed in the Louvre Museum in Paris and is protected as a cultural and historical treasure.

5. What makes the Mona Lisa's smile so mysterious?

Leonardo used the sfumato technique to blur the lines around her mouth and eyes, creating an expression that changes depending on the viewer’s perspective. This ambiguity has captivated audiences for centuries.

6. Why doesn't the Mona Lisa have eyebrows?

There is debate over whether the Mona Lisa originally had eyebrows. Some suggest they were removed during restoration, while others believe Leonardo left them out to enhance the painting’s ethereal quality.

7. Has the Mona Lisa ever been stolen?

Yes, the Mona Lisa was famously stolen in 1911 by Vincenzo Peruggia, an Italian handyman. She was recovered two years later and has been heavily protected ever since.

8. Why is the Mona Lisa so small?

The painting measures approximately 77 cm by 53 cm (30 inches by 21 inches). Many visitors are surprised by its modest size compared to its immense reputation.

9. What materials were used to create the Mona Lisa?

Leonardo painted the Mona Lisa using oil paints on a poplar wood panel, a common material during the Renaissance.

10. Are there other versions of the Mona Lisa?

Yes, several versions and copies of the Mona Lisa exist, including the Prado Museum’s version, believed to have been created by one of Leonardo’s students.

11. What is the significance of the Mona Lisa's background?

The background features an imaginary landscape with winding paths and a distant horizon, blending seamlessly with the subject. This contributes to the painting’s depth and timeless quality.

12. Did Leonardo da Vinci sign the Mona Lisa?

No, Leonardo did not sign or date the Mona Lisa, which was not unusual for artists of his time. Its attribution is based on historical documentation and stylistic analysis.

13. How is the Mona Lisa preserved?

The painting is displayed in a bulletproof, climate-controlled glass case to protect it from environmental damage and vandalism.

14. Has the Mona Lisa ever left the Louvre Museum?

Yes, the Mona Lisa has traveled for exhibitions, including notable displays in the United States in 1963 and in Japan and Russia in 1974. However, due to its delicate state, it is unlikely to travel again.

15. Why is the Mona Lisa called "La Gioconda"?

"La Gioconda" is the Italian name for the painting, referring to Lisa Gherardini’s married name, Lisa del Giocondo. In Italian, "gioconda" also means "light-hearted," reflecting her expression.

16. What is the Mona Lisa’s current value?

The Mona Lisa was insured for $100 million in 1962, which is approximately $1 billion today. However, it is considered priceless and cannot be sold.

17. Has the Mona Lisa ever been damaged?

Yes, the painting has faced attacks, including acid damage and a rock-throwing incident in 1956. Protective glass now shields it from harm.

18. What is the Mona Lisa’s historical significance?

The painting is a pinnacle of Renaissance art and demonstrates Leonardo’s mastery of anatomy, perspective, and emotion, making it a key cultural and artistic milestone.

19. How did the Mona Lisa influence popular culture?

The Mona Lisa has inspired countless references in movies, music, literature, and art, from Marcel Duchamp’s "L.H.O.O.Q." to appearances in pop songs and films.

20. Why is the perspective in the Mona Lisa’s background uneven?

The background appears asymmetrical, with the horizon line higher on one side. This intentional design adds an optical illusion and a sense of movement, showcasing Leonardo’s innovation.

21. Did Leonardo create the Mona Lisa entirely alone?

While the Mona Lisa is primarily Leonardo’s work, some believe his students assisted in minor details. However, its mastery is attributed to Leonardo’s genius.

22. What is the connection between the Mona Lisa and Leonardo’s self-portrait?

Some researchers, like Lillian Schwartz, have noted similarities between the Mona Lisa’s face and Leonardo’s self-portrait, suggesting he may have infused aspects of himself into the painting.

23. What was the Mona Lisa originally called?

Before being titled the "Mona Lisa," the painting was referred to by names such as "A Certain Florentine Lady" and "La Joconde" in different historical texts.

24. How many layers of paint does the Mona Lisa have?

Advanced imaging reveals the painting has thousands of ultra-thin layers of paint, showcasing Leonardo’s painstaking attention to detail.

25. Can the Mona Lisa's secrets still be uncovered?

Modern technology, such as multispectral imaging, continues to reveal new details about the Mona Lisa, from hidden layers to insights into Leonardo’s techniques, proving that her mysteries endure.