St Anne Cartoon

The Virgin and Child with St Anne and St John the Baptist

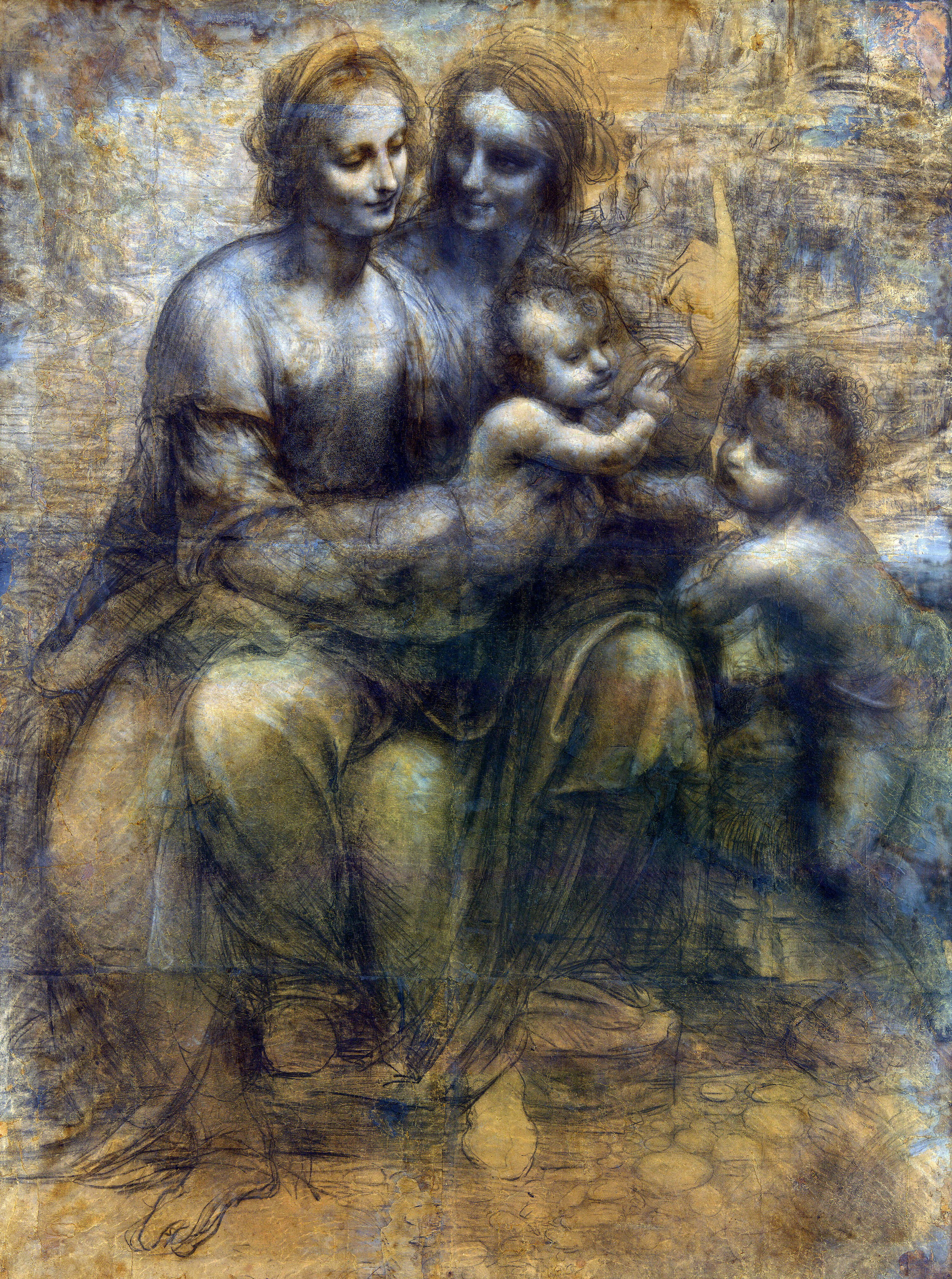

The Virgin and Child with St Anne and St John the Baptist, sometimes called The Burlington House Cartoon, is a drawing by Leonardo da Vinci. The drawing is in charcoal and black and whitechalk, on eight sheets of paper glued together. Because of its large size and format the drawing is presumed to be a cartoon for a painting. No painting by Leonardo exists that is based directly on this cartoon.

The drawing depicts the Virgin Mary seated on the knees of her mother St Anne and holding the Child Jesus while St. John the Baptist, the cousin of Jesus, stands to the right. It currently hangs in theNational Gallery in London. It was either executed in around 1499–1500, at the end of the artist's first Milanese period, or around 1506–8, when he was shuttling between Florence and Milan; the majority of scholars prefer the latter date, although the National Gallery and others prefer the former.[1]

Subject

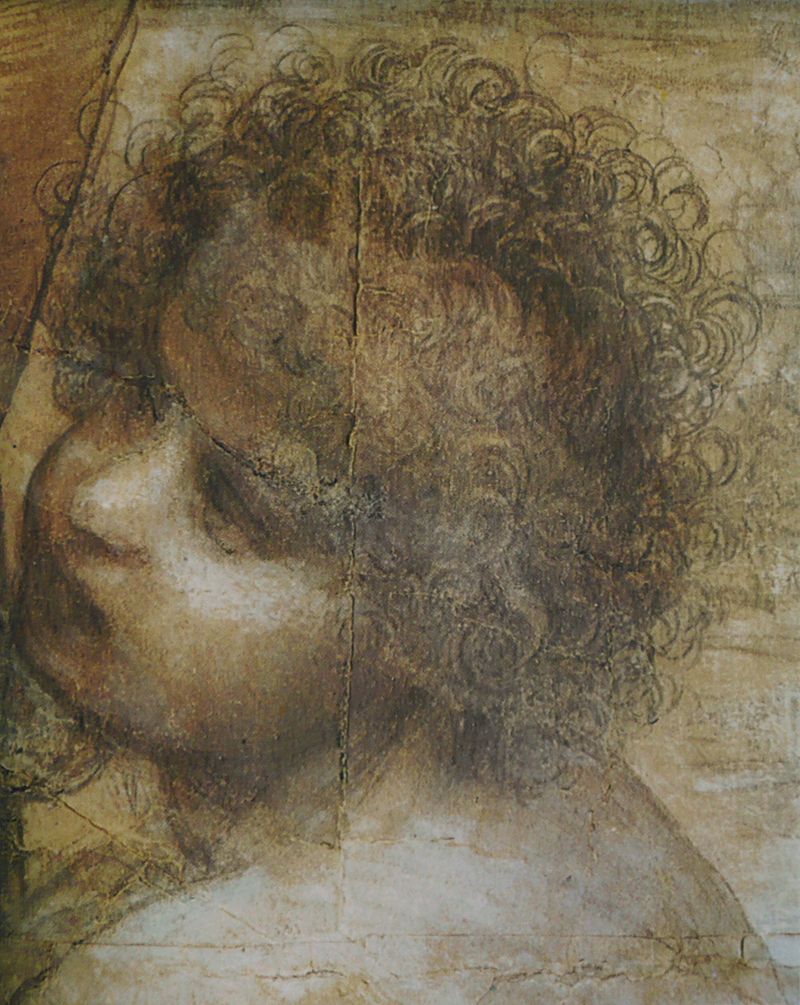

Preparatory drawing in theBritish Museum, London

The subject of the cartoon is a combination of two themes popular in Florentine painting of the 15th century: The Virgin and Child with John the Baptist and The Virgin and Child with St Anne.

The drawing is notable for its complex composition, demonstrating the alternation in the positioning of figures that is first apparent in Leonardo's paintings in the Benois Madonna. The knees of the two women point different directions, with Mary's knees turning out of the painting to the left, while her body turns sharply to the right, creating a sinuous movement. The knees and the feet of the figures establish a strong up-and-down rhythm at a point in the composition where a firm foundation comprising firmly planted feet, widely spread knees and broad spread of enclosing garment would normally be found. While the lower halves of their bodies turn away, the faces of the two women turn towards each other, mirroring each other's features. The delineation between the upper bodies has lost clarity, suggesting that the heads are part of the same body.

The twisting movement of the Virgin is echoed in the Christ Child, whose body, held almost horizontal by his mother, rotates axially, with the lower body turned upward and the upper body turned downward. This turning posture is first indicated in Leonardo's painting in the Adoration of the Magi and is explored in a number of drawings, in particular the various studies of the Virgin and Child with a cat that are in the British Museum.

The juxtaposition of two sets of heads is an important compositional element. The angle, lighting and gaze of the Christ Child reproduces that of his mother, while John the Baptist reproduces these same elements in the face of St Anne. The lighting indicates that there are two protagonists, and two supporting cast in the scene that the viewer is witnessing. There is a subtle interplay between the gazes of the four figures. St Anne smiles adoringly at her daughter Mary, perhaps indicating not only maternal pride but also the veneration due to the one who "all generations will call...blessed".[2] Mary's eyes are fixed on the Christ Child who raises his hand in a gesture of benediction over the cousin who thirty years later would carry out his appointed task of baptising Jesus. Although the older of the two children, John the Baptist humbly accepts the blessing, as one who would later say of his cousin "I am not worthy even to unloose his sandals." [3] St Anne's hand, her index finger pointing towards the Heaven, is positioned near the heads of the children, perhaps to indicate the original source of the blessing. This enigmatic gesture is regarded as quintessentially Leonardesque, occurring in the Last Supper and St John the Baptist.

Cartoons of this sort were usually transferred to a board for painting by pricking or incising the outline. In the Virgin and Child with St Anne and St John the Baptist this has not been done, suggesting that the drawing has been kept as a work of art in its own right.[4] Leonardo does not appear to have based a painting directly on this drawing. The composition differs from Leonardo's only other surviving treatment of the subject, The Virgin and Child with St. Anne in the Louvre, in which the figure of the Baptist is not present. A painting based on the cartoon was made by a pupil of Leonardo, Bernardino Luini, and is now in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan.[5]The figure of Pomona in Francesco Melzi's painting Pomona and Vertumnus in Berlin is based upon the Virgin in the cartoon.

History

The date and place of execution of the cartoon is disputed. The earliest reference to it is by the biographer Giorgio Vasari who, writing in the mid 16th century, says that the work was created while Leonardo was inFlorence, as a guest of the Servite Monastery. Vasari says that for two days people young and old flocked to see the drawing as if they were attending a festival.[6] This would date the cartoon to about 1500.

A date of 1498-99 is put on the work by Padre Sebastiano Resta who wrote to Giovanni Pietro Bellori saying that Leonardo had drawn the cartoon in Milan at the request of Louis XII of France. While this date has gained wide acceptance, the association with Louis XII has not. More recent historians have dated the work as early as the mid 1490s and, in the case of Carlo Pedretti and Kenneth Clark, as late as 1508-10.[7] Martin Kemp notes that the hydraulic engineering in the preparatory drawing in the British Museum dates the composition to around 1507–8, when Leonardo was making similar studies in the Codex Atlanticus.[8]

In the 17th century the drawing belonged to the Counts Arconati of Milan. In 1721 it passed to the Casnedis, then to the Sagredo in Venice. In 1763 it was acquired by Robert Udny, brother of the English ambassador to Venice. By 1791 it was inventoried as belonging to the Royal Academy, London.[5] It is sometimes still known as "The Burlington House Cartoon", in reference to the building housing the Royal Academy.

In 1962 the cartoon was put on sale for £800,000.[9] Amid fears that it would find an overseas buyer, it was exhibited in the National Gallery where it was seen by over a quarter of a million people in a little over four months, many of whom made donations in order to keep it in the United Kingdom.[10] The price was eventually met, thanks in part to contributions from the National Art Collections Fund. Ten years after its acquisition, John Berger wrote derisively that "It has acquired a new kind of impressiveness. Not because of what it shows – not because of the meaning of its image. It has become impressive, mysterious because of its market value".[11] In 1987, the cartoon was attacked in an act of vandalism with a sawn-off shotgun from a distance of approximately seven feet. The shooter was identified as a mentally ill man by the name of Robert Cambridge who claimed he committed this act in order to bring attention to "political, social and economic conditions in Britain." The blast shattered the glass covering, causing significant damage to the artwork which has since been restored.[12]

- Wikipedia